The World of Monteverdi – Mantua and Venice – Extract from talk given to Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane.

The World of Monteverdi – Mantua and Venice – Extract from talk given to Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane.

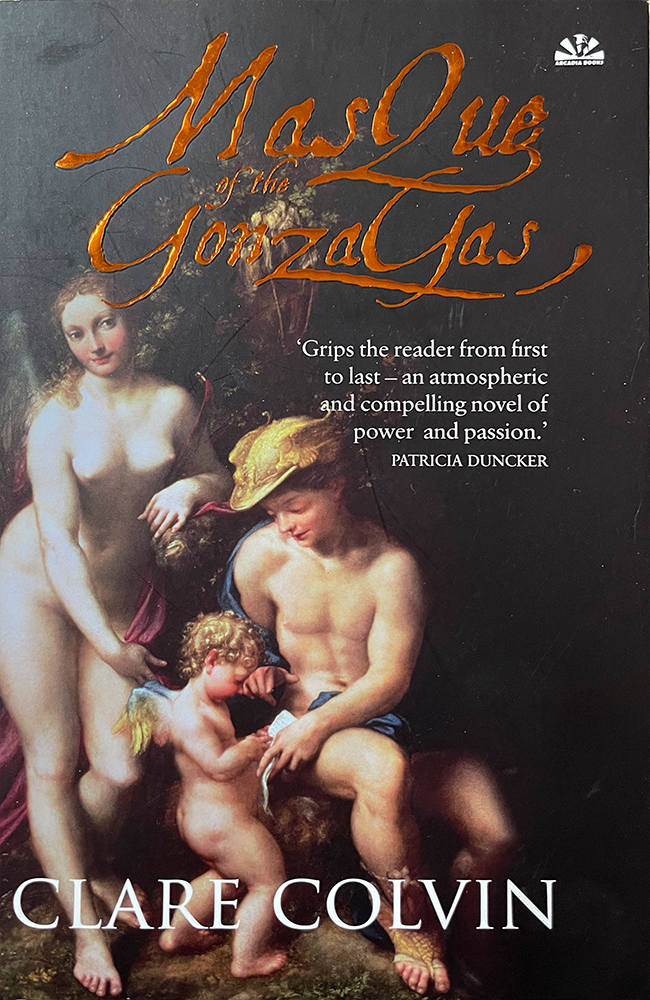

The seed for a novel is often sown many years before by a chance remark or image that stays in the mind, until something else sparks it into life. With Masque of the Gonzagas, it began when I was told years ago by a friend who had visited the ducal palace in Mantua of a miniature set of apartments which the Duke had built for his dwarfs.

This image stayed with me for some reason, until one day I read that Claudio Monteverdi, a composer whose music I felt great empathy with, had been court composer to this crazy dwarf-loving Duke. It didn’t matter that when I went to Mantua eventually I found out that the miniature apartments had been built for another, though equally odd, reason. The important thing to me was the connection between this extravagant prince with eccentric ideas and the musical genius who led the way from Renaissance polyphony to the baroque era, and to opera.

One reason for remembering Monteverdi now is that 2007 is the 400th anniversary of the first operatic masterpiece Orfeo, performed at the ducal palace in Mantua in February 1607. It’s unique in that it’s still performed today when so many later operas are forgotten.

Monteverdi’s working life was divided into two parts – the earlier part as court composer for the Duke of Mantua, and then in his middle years, in Venice where he was Director of Music at St Mark’s from 13 Aug 1613 until his death in 1643. He revitalised Venice’s musical scene and Venice, in return, provided him with the security he needed, mainly that of being paid on time and not having to accommodate the changeable moods of one man. But I think Mantua provided the fertile ground of life’s experience, and without having gone through some tempestuous years there, he might have written a less passionately involved Coronation of Poppea, for instance. He knew about the whims of absolute rulers at first hand.

The fourth Duke of Mantua, Vincenzo Gonzaga, could have been a model for the Duke in Verdi’s Rigoletto. A notorious libertine, a gambler, a restless traveller and a voracious seeker after culture, his reign was a glorious 25 year spree of theatrical extravaganzas, huge sums spent on paintings by Italian masters, and quixotic crusades against the Turk in Hungary. He shared an interest in alchemy with Emperor Rudolf. He maintained a theatrical troupe of dwarfs, a resident company of actors, and another company of musicians and singers, which from 1600 until the Duke’s death in 1612 was under the directorship of Claudio Monteverdi.

Imagine the scene on that cold evening in Mantua on 24 February 1607, the mist rising from the lake surrounding the city, the huge ducal palace with its maze of corridors, apartments and courtyards, a veritable city in itself. There is no record of exactly which room Orfeo was performed in, merely that it was in the apartments formerly occupied by the Duke’s sister, the Duchess of Ferrara. Monteverdi’s Friday concerts for which he would write new music each week, were held in a room called the Hall of Mirrors, which was smaller than the Hall of Mirrors that exists today. The opera was performed as part of the Carnival celebrations and was an immediate hit.

Although Orfeo is regarded as the first operatic masterpiece, the Florentines had already taken the idea of performing a drama to music, seeking, in Humanist style, to revive performing practices thought to have been in use in the drama of ancient Greece and Rome. The first opera to survive complete, Jacopo Peri’s Euridice was performed to celebrate the wedding of Marie de’Medici to Henry IV of France in Florence in 1600. The Duke of Mantua was a guest and his retinue included his court secretary Alessandro Striggio, the librettist of Orfeo. Whether Monteverdi was present on that occasion or not, it is clear that he and Striggio were setting themselves up in competition with the Florentines, encouraged by the Gonzagas in supporting the first performance.

There’s a comment in a letter from Ottavio Rinuccini, the librettist of Monteverdi’s second opera Arianna, writing during the long and involved rehearsals, that neatly sums up the new art form: “These sung things are more difficult and more beautiful than people think; they require great exquisiteness, otherwise they do not succeed.”

Years later, when Monteverdi was in Venice, he defined the special quality of his operatic work, referring to Orfeo and Arianna, when the Mantuan court tried to commission another opera from him. The mythical subject of Le Nozze di Tetide failed to attract him, he said, as he could not for the life of him think how the elements should sing. “How, dear Sir, can I imitate the speech of the winds, if they do not speak? And how can I, by such means, move the passions? Ariadne moved us because she was a woman, and similarly Orpheus because he was a man, not a wind. Music can suggest, without any words, the noise of winds and the bleating of sheep, the neighing of horses, and so on. But it cannot imitate the speech of winds because no such thing exists.”

Years later, when Monteverdi was in Venice, he defined the special quality of his operatic work, referring to Orfeo and Arianna, when the Mantuan court tried to commission another opera from him. The mythical subject of Le Nozze di Tetide failed to attract him, he said, as he could not for the life of him think how the elements should sing. “How, dear Sir, can I imitate the speech of the winds, if they do not speak? And how can I, by such means, move the passions? Ariadne moved us because she was a woman, and similarly Orpheus because he was a man, not a wind. Music can suggest, without any words, the noise of winds and the bleating of sheep, the neighing of horses, and so on. But it cannot imitate the speech of winds because no such thing exists.”

This sums up Monteverdi’s empathy with the link between human emotion and music, and is one reason why his first opera survived through the centuries – no doubt Arianna would have done so, too, had the score not been lost.

After years of writing mainly liturgical music in Venice, Monteverdi’s interest in opera found new expression with the arrival of two composers and singers from Rome, fleeing from the politics of the papal state. He snapped them up for St Mark’s, though he knew they were not principally interested in church music. In 1637 the first public opera house opened, the converted theatre of San Cassiano, near the Rialto. For the first time it was possible to buy a ticket of admission, rather than to be invited as a guest of a noble patron. Monteverdi realised its potential and he revived Arianna, at the Teatro San Moise, near the Piazza San Marco, followed by at least two new works The Return of Ulysses, which was produced at the San Cassiano, and The Marriage of Aeneas and Lavinia which was put on at the Teatro SS Giovanni e Paolo on the Fondamente Nuove. Finally, at the age of 75, he composed his greatest masterpiece, L’incoronazione di Poppea, which opened to packed houses at the Teatro SS Giovanni e Paolo in 1642.

In this opera, you can sense Monteverdi’s knowledge of the Mantuan court being drawn on, particularly the spirit of Duke Vincenzo. As you listen to the music of Nero, careless, capricious, sensual, you realise it was a character with which the composer was familiar.

A few months after the triumphant performance of Poppea, Monteverdi went on a prolonged tour of Lombardy and Mantua, where he tried yet again to chase up the pension he had been promised several Dukes before. It may have been the unhealthy air of Mantua that caused his final illness. He caught a fever and died in Venice in November 1643 at the age of 76.

Monteverdi’s tomb is to be found in the Lombardy Chapel of Santa Maria Gloriosa de Frari at the Campo San Polo. It’s a plain slab on the floor with his name and dates, and often there is a single red rose lying on the tomb. His music lives on – rediscovered in the mid-twentieth century after years of neglect .

© Clare Colvin

Click here to read the reviews

click here to read an extract from the book

buy the book from amazon.com

buy the book from amazon.co.uk